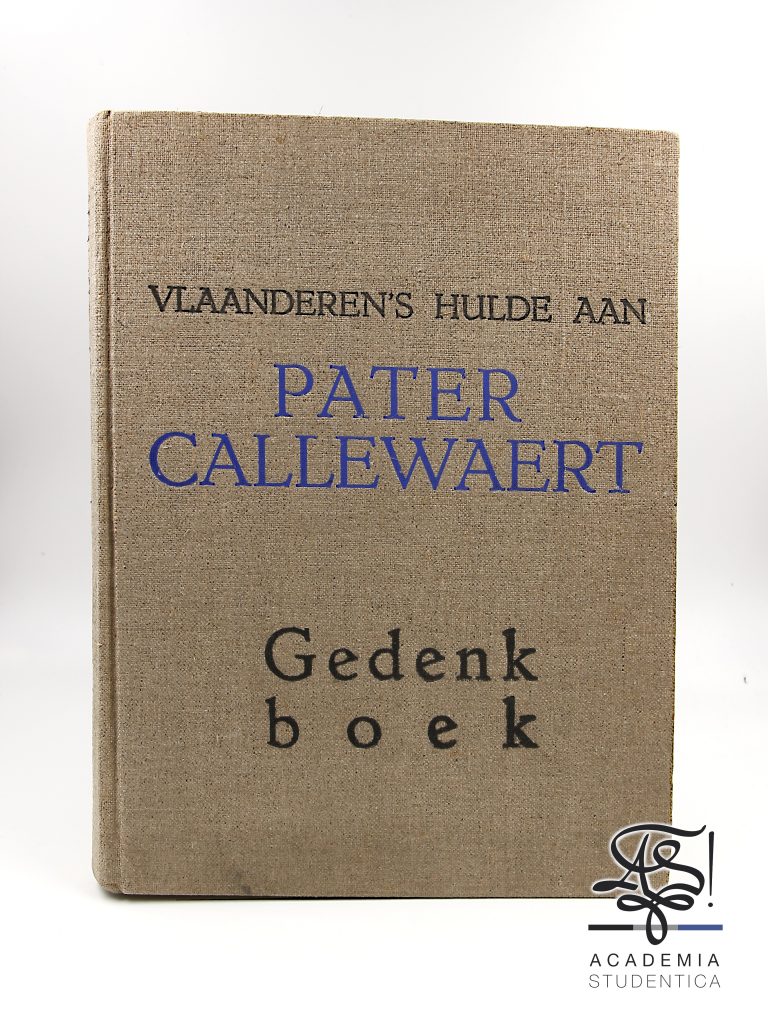

Brouns, Theo, Vlaanderen’s Hulde aan Pater Callewaert Gedenkboek, Drukkerij Steenlandt, Belgium, Kortrijk, 1936.

Coll.: Cap’n

Father Julius L. Callewaert (°Torhout, 1886 – +1964, Ghent) was a Flemish Dominican and a writer and was best known for his Flemish-nationalist commitment.

He studied at the “Minor Seminary” in Roeselare and then went to Leuven where he studied philosophy and theology. Because of this he excelled as a preacher. In 1912 he was ordained as a priest.

At the outbreak of the First World War he fled to England where he wrote for magazines for the Flemish soldiers at the front. In 1919 he joined the Front Movement. This made him persona non grata for the Belgian authorities and he was asked by the Church to hold a period of reflection in Dublin, which in fact amounted to an exile. After his return from Dublin he profiled himself as an independent, Flemish, Christian thinker with a well-defined vision on youth and education.

During the twenties he became a leading figure within the Flemish movement and in the thirties he became involved in the VNV, the “Vlaamsch Nationalistisch Verbond”.

In September 1939, a few days after the German invasion of Poland, Callewaert started his War Diary. In the first part of his diary, he plays with the idea that it is a historical law that God intervenes in the world every now and then and destroys it in order to build a new one, as in the story of Noah and the Ark. He openly admired the Nazi regime and Adolf Hitler. When the German troops occupied Belgium, he was initially enthusiastic.

He decided to assess the war events and the policy of the Germans on the basis of two principles: the position of Catholicism and the independence of Flanders. However, Callewaert was soon disappointed with his first principle: Nazi ideology was diametrically opposed to the Catholic faith. As for his second principle, the independence of Flanders, his expectations remained high. Throughout the war years, his distrust of the German occupation would increase because of the many promises for an independent Flemish state that were not fulfilled. After the German defeat at Stalingrad in the winter of 1942, Callewaert’s belief in a German final victory had almost disappeared and he became convinced that he had to do something to lead Flanders and Catholicism out of this crisis. However, his definitive reversal and aversion to collaboration came late and only after the Germans were forced into the defensive.

His attitude during the Second World War and his appeals to the Flemish youth to fight against the Bolsheviks in Russia caused him to end up in an internment camp in 1945 and in 1946 he was court-martialed. The court-martial officer sentenced him to 6 years imprisonment, but rejected the claim for compensation from the Belgian state.

Days later Callewaert appealed and reappeared before the court-martial. After one hearing, he was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment.

Two years after the war, he spent some time in prison. Afterwards he spent about a year and a half in Italy, but in 1950 Father Callewaert was again in the monastery of Ghent.

He had health problems in the sixties and died in Ghent in 1964.

On pages 484 or 495 of the Flemish Student Codex, depending on the year of publication, you will find the “Song of Father Callewaert”, which gives a brief impression of his beliefs on a Catholic and Flemish level.

Brouns, Theo, Vlaanderen’s Hulde aan Pater Callewaert Gedenkboek, Drukkerij Steenlandt, Belgique, Kortrijk, 1936.

Coll.: Cap’n

Le père Julius L. Callewaert (°Torhout, 1886 – +1964, Gand) était un dominicain flamand et un écrivain et était surtout connu pour son engagement nationaliste flamand.

Il a étudié au “Petit Séminaire” de Roulers, puis est allé à Louvain où il a étudié la philosophie et la théologie. C’est pour cette raison qu’il a excellé en tant que prédicateur. En 1912, il est ordonné prêtre.

Au début de la Première Guerre mondiale, il s’enfuit en Angleterre où il écrit des magazines pour les soldats flamands au front. En 1919, il rejoint le Mouvement du Front. Cela le rend persona non grata pour les autorités belges et l’Église lui demande de tenir une période de réflexion à Dublin, ce qui équivaut en fait à un exil. Après son retour de Dublin, il s’est profilé comme un penseur indépendant, flamand et chrétien avec une vision bien définie sur la jeunesse et l’éducation.

Dans les années vingt, il est devenu une figure de proue du mouvement flamand et dans les années trente, il s’est engagé dans le VNV, le Vlaamsch Nationalistisch Verbond.

En septembre 1939, quelques jours après l’invasion allemande de la Pologne, Callewaert a commencé son journal de guerre. Dans la première partie de son journal, il joue avec l’idée que c’est une loi historique que Dieu intervient dans le monde de temps en temps et le détruit pour en construire un nouveau, comme dans l’histoire de Noé et de l’Arche. Il admirait ouvertement le régime nazi et Adolf Hitler. Lorsque les troupes allemandes ont occupé la Belgique, il a d’abord été enthousiaste.

Il décide d’évaluer les événements de la guerre et la politique des Allemands sur la base de deux principes : la position du catholicisme et l’indépendance de la Flandre. Cependant, Callewaert fut bientôt déçu par son premier principe : l’idéologie nazie était diamétralement opposée à la foi catholique. Quant à son deuxième principe, l’indépendance de la Flandre, ses attentes restent élevées. Pendant les années de guerre, sa méfiance à l’égard de l’occupation allemande va s’accroître en raison des nombreuses promesses d’un État flamand indépendant. Après la défaite allemande à Stalingrad à l’hiver 1942, la croyance de Callewaert en une victoire finale allemande avait presque disparu et il devint convaincu qu’il devait faire quelque chose pour sortir la Flandre et le catholicisme de cette crise. Cependant, son revirement définitif et son aversion pour la collaboration sont arrivés tardivement et seulement après que les Allemands aient été forcés de se mettre sur la défensive.

Son attitude pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale et ses appels à la jeunesse flamande pour qu’elle lutte contre les bolcheviks en Russie lui valent de se retrouver dans un camp d’internement en 1945 et de passer en cour martiale en 1946. L’officier de la cour martiale l’a condamné à 6 ans de prison, mais a rejeté la demande d’indemnisation de l’État belge.

Le lendemain, Callewaert fait appel et comparaît à nouveau devant la cour martiale. Après une seule audience, il a été condamné à 12 ans de prison.

Deux ans après la guerre, il a passé un certain temps en prison. Il a ensuite passé environ un an et demi en Italie, mais en 1950, le père Callewaert était de nouveau au monastère de Gand.

Il a eu des problèmes de santé dans les années 60 et est mort à Gand en 1964.

Aux pages 484 ou 495 du Code flamand des étudiants, selon l’année, vous trouverez le “Chant du père Callewaert”, qui donne un bref aperçu de ses convictions au niveau catholique et flamand.

Brouns, Theo, Vlaanderen’s Hulde aan Pater Callewaert Gedenkboek, Drukkerij Steenlandt, België, Kortrijk, 1936.

Coll.: Cap’n

Pater Julius L. Callewaert (°Torhout, 1886 – +1964, Gent) was een Vlaams dominicaan en schrijver en was vooral gekend voor zijn Vlaams-nationalistisch engagement.

Hij studeerde aan het “Klein Seminarie” in Roeselare en ging nadien naar Leuven waar hij filosofie en theologie studeerde. Hierdoor blonk hij uit als predikant. In 1912 werd hij tot priester gewijd.

Bij het uitbreken van de eerste wereldoorlog vluchtte hij naar Engeland waar hij schreef voor tijdschriften voor de Vlaamse soldaten aan het front. In 1919 sloot hij zich aan bij de Frontbeweging. Dit maakte hem persona non grata voor de Belgische autoriteiten en hij werd door de kerk gevraagd om een bezinningsperiode te houden in Dublin, wat in feite neerkwam op een verbanning. Na zijn terugkeer uit Dublin profileert hij zich als een onafhankelijke, Vlaamse, christelijke denker met een welomlijnde visie op jeugd en opvoedkunde.

Gedurende de jaren ’20 groeide hij uit tot een toonaangevend figuur binnen de Vlaamse beweging en in de jaren ’30 raakte hij betrokken bij het VNV, het Vlaamsch Nationalistisch Verbond.

In september 1939, enkele dagen na de Duitse inval in Polen, begon Callewaert aan zijn Oorlogsdagboek. In het eerste deel van zijn dagboek speelt hij met het idee dat het een geschiedkundige wetmatigheid is dat God om de zoveel tijd ingrijpt in de wereld en deze vernielt om er een nieuwe op te kunnen bouwen, zoals in het verhaal van Noah en de Ark. Hij bewonderde openlijk het Nazistisch regime en Adolf Hitler. Toen de Duitse troepen België bezetten, was hij aanvankelijk dan ook enthousiast.

Hij besloot de oorlogsgebeurtenissen en het beleid van de Duitsers te beoordelen aan de hand van twee principes: de positie van het katholicisme en de zelfstandigheid van Vlaanderen. Callewaert werd echter al snel teleurgesteld wat betreft zijn eerste principe: de nazi-ideologie stond namelijk lijnrecht tegenover het katholiek geloof. Op het vlak van zijn tweede principe, de onafhankelijkheid van Vlaanderen, bleven zijn verwachtingen wél hoog gespannen. Doorheen de oorlogsjaren zou zijn wantrouwen jegens de Duitse bezetting toenemen doordat er van de vele beloftes voor een onafhankelijke Vlaamse staat niets in huis kwam. Na de Duitse nederlaag bij Stalingrad in de winter van 1942, was Callewaerts geloof in een Duitse eindoverwinning nagenoeg verdwenen en raakte hij ervan overtuigd dat hij iets moest doen om Vlaanderen en het katholicisme uit deze crisis te leiden. Zijn definitieve ommekeer en afkeer van de collaboratie kwamen echter laat en pas nadat de Duitsers in het defensief gedwongen werden.

Zijn houding gedurende de tweede wereldoorlog en zijn oproepen aan de Vlaamse jeugd om in Rusland tegen de Bolsjewieken te gaan strijden, zorgden ervoor dat hij in 1945 in een interneringskamp terecht kwam en in 1946 verscheen hij voor de krijgsraad. De krijgsauditeur veroordeelde hem tot 6 jaar hechtenis, maar wees de eis tot vergoeding vanwege de Belgische staat af.

Daags nadien ging Callewaert in hoger beroep en verscheen opnieuw voor het Krijgshof. Na één zitting volgde de uitspraak: 12 jaar hechtenis.

2 Jaar na de oorlog heeft hij enige tijd in de gevangenis gezeten. Nadien heeft hij ongeveer anderhalf jaar in Italië doorgebracht, maar in 1950 was pater Callewaert opnieuw in het Gentse klooster.

Hij kampte in de jaren ’60 met gezondheidsproblemen en overleed in 1964 te Gent.

In de Vlaamse Studentencodex vind je op pagina 484 of 495, afhankelijk van de jaargang, het “Lied van Pater Callewaert” wat een summier beeld geeft van zijn overtuigingen op Katholiek en Vlaams vlak.